Shanti Kumar | Technical Advisor, Program Design and Impact

The wide-reaching and durable impacts of Graduation programs are often attributed to the multifaceted set of interventions that make up the approach. The sequence of their delivery is less often considered, though just as critical as the interventions themselves.

Sequencing, also known as timing or layering, refers to the order of events in the delivery of a Graduation program. Proper sequencing of interventions is critical for a successful program as it ensures participants fully benefit from each key component of the “big push” out of extreme poverty. Correct sequencing reduces participant attrition, supports coordination with government services, and enhances overall program impact because the components reinforce each other and build resilience to future shocks.

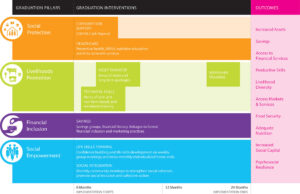

BRAC conceptualizes the Graduation approach as having four foundational pillars, yet these pillars are not a sequence or an order on their own. Interventions that happen at different times in the program cycle can fall under the same pillar. For example, consumption support is often required at the very beginning of implementation to ensure people’s most basic needs are met before they receive training of any kind. However, the social protection pillar remains relevant throughout the program cycle and returns at the end when participants are linked to higher order social services after they exit the program like higher education and microfinance.

While adapting Graduation interventions to each context is encouraged for a strong program, the principles of sequencing Graduation interventions remain fairly consistent in each program. The following is not a prescriptive order of interventions, but rather a series of considerations for program designers seeking to sequence interventions most effectively:

Pre-implementation

- Assessment & Targeting – The assessment and targeting phases are when participant characteristics (demography, geography, productive capacity) are determined, and participants are selected from a larger population. Information gathered during this period about the conditions and challenges faced by participants should directly influence the design of program interventions. For example, the Market Assessment (which assesses existing and potential livelihood opportunities) should result in a “menu” of livelihood options for participants to choose from and also inform what kind of livelihoods/business training coaches must be prepared to offer.

Implementation

- Consumption support usually takes the form of a monthly cash transfer to meet a households’ basic needs, mainly purchasing food. This support for basic needs must predate the asset transfer as to avoid a situation in which the household sells off of their new productive asset in order to meet their basic needs, and thus remains in the poverty trap. BRAC recommends aligning schedules with existing cash transfer programs, which may have specific enrollment periods or experience delays. A first implementation activity is often registering Graduation participants into these ongoing cash transfer programs and addressing barriers disbursement.

- Early on, households should be linked to basic services such as education for school-aged children, healthcare/insurance, and to housing or water and sanitation services (WASH) where relevant. Only once these basic needs are met can the household focus their energy on growing a viable livelihood.

- Based on the menu of livelihoods developed through the earlier Market Assessment and consultations with coaches, households undergo the process of livelihood selection. Livelihoods are selected based on household interest, skills, existing assets, and market conditions.

- Technical training in livelihoods must predate the transfer of productive assets to households. This is to ensure that households have some level of knowledge prior to receiving their productive asset and starting their livelihood as to avoid early but catastrophic errors in asset care. Technical training returns later in the program cycle with refresher training (for both staff and participants) focused on maturing livelihoods.

- When the productive asset is transferred, it is essential for many agricultural or livestock-based assets that the timing of the transfer seasonally aligns with the production cycle. “Large and lumpy” asset transfers mean that they are sizable enough to jumpstart a livelihood and indivisible to avoid offselling. While most programs utilize a one-time asset transfer, some divide it into two conditional transfers. The second tranche arrives as an infusion of capital to maintain or build momentum in a livelihood’s growth.

- As incomes rise from growing livelihoods, participants should be supported to save and access credit through informal savings groups, improve their financial literacy skills to better manage income and expenditures, and eventually be connected with formal banking services. Towards the close of a program, savings groups should be evaluated for their ability to continue meeting without the support of their coach, and embedded with the confidence and capacity to do so. Savings groups that continue to meet post-Graduation are one of the ways program impacts can be maintained in the long term, as they serve as a combination of self-sustaining economic and social support.

- Life skills training and social empowerment are delivered through a combination of group sessions, individual mentorship, and peer-to-peer learning throughout the program. A well-structured life skills training curriculum prioritizes basic and straightforward skills earlier in the program cycle, such as nutrition, WASH, and waste management. Later in the program once more trust is built, coaches introduce complex or controversial topics such as gender-based violence, disaster risk reduction, family planning, FGM, or child marriage. All group trainings should be reinforced through refreshers and individual household visits. Towards the end of the program, coaches should use household visits as opportunities to prepare participants for life post-Graduation and discuss what concerns they may have.

- Though the first step of implementation begins with social protection through consumption support, it also ends with social protection through connections to higher order services such as micro-credit institutions, livestock insurance, and higher levels of vocational or educational training. Timing is important here because by the time participants “graduate” they are able to make use of these services, and the final role of their coach may be in connecting them with those most relevant to their newfound situation.

The risks of not sequencing Graduation components properly can threaten the impact of the entire program, whether it be due to untimely gaps between interventions, rushing through interventions, or delivering them in an illogical order. For example, Graduation participants given robust technical skills and business training who remain waiting for their productive asset transfer for too long may lose trust in the program and begin to drop out or forget their training. The inverse is also true, as participants who are given their productive asset with no level of technical knowledge may jeopardize the health of their asset by making a critical error at the start (e.g. not having sufficient shelter from the elements for livestock, lacking vaccinations, lacking proper equipment, etc.). These sequencing errors can cause Graduation outcomes to plummet, participants lost to attrition, and leave remaining participants unable to utilize fragmented pieces of the “big push” that Graduation is known for.

Sequencing has the ability to “make or break” a Graduation program, and it is for this reason that everything should be done from program inception to evaluation in order to ensure it is done in the most ideal manner possible. The goal of “big push” approaches like Graduation is to set up participants for success long after they exit formal program interventions, with resilience building being a key to their upward trajectories. To learn more about sequencing, designing, and delivering transformative government-led Graduation programs, read the recent PEI In Practice publication. By purposefully building a comprehensive and holistic program where participants are given every opportunity to succeed along the way, program designers and implementers can ensure that no one is left behind in the process.