BRAC’s Ultra-Poor Graduation Initiative is working to help scale up Graduation through governments with an audacious goal of reaching 21 million people. To reach that scale, we are continuously consulting the literature and gathering feedback from deeply experienced implementers at BRAC and beyond on how to scale more effectively.

We recently engaged in an exercise to identify the most essential components of the Graduation approach. To do this, we conducted an evidence review and gathered internal feedback from our practitioners to gut-check the findings.

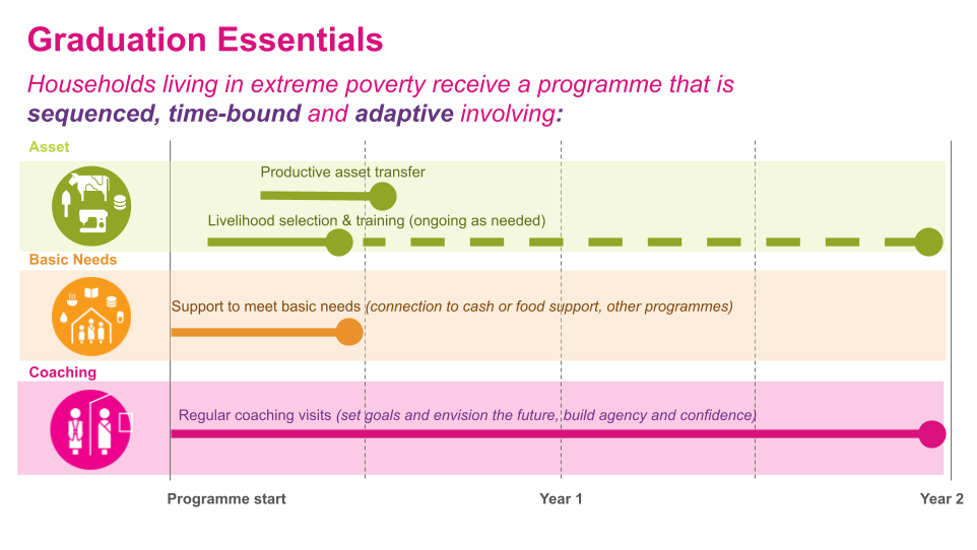

What emerged are three must-have elements that we’re calling the Graduation Essentials, or “ABCs”: a productive asset (or lump sum cash), support for basic needs, and coaching that unlocks agency, know-how, and hope.

Why do we need “essentials”?

We needed essentials for two key reasons. One, in the past, some have interpreted Graduation to mean any program with a set of components designed to alleviate poverty. This misinterpretation has led to large-scale implementation of programs called “Graduation” that do not feature critical components of the approach and are, therefore, unlikely to have similar impacts. We wanted to clarify what Graduation is, and is not.

Second, budget-constrained implementers – and governments especially – need to know which elements of this multifaceted approach to prioritize in their scaling agendas.

They need to know the essentials not only to ensure the highest return on investment possible, but also to maximize feasibility for scale. Research shows that simpler programs are easier to scale – this has been demonstrated across a large number of approaches and evidence from the world’s foremost scaling experts concludes that it’s just easier to make mistakes and hit roadblocks when implementing complex programs.

The idea of Graduation was – and still is – to tackle multiple barriers to overcoming poverty together. But now, with nearly 30 randomized evaluations on the Graduation approach over almost two decades of implementation, we not only have the experience but also the evidence to know which barriers are the most important to tackle for households to escape the poverty trap.

The Graduation Essentials

This framework does not mean that effective programs should not include other components. Rather, these three elements make up the most bare-bones version that works.

In brief, here is how we define the the “ABCs”:

- Asset: A grant or investment given to the participant that is large enough to establish a sustainable, lasting livelihood.

This is now most often delivered as a labeled lump sum cash payment, but was historically a physical asset (a cow, some goats, a sewing machine, or start-up capital for a corner store, for example). Researchers we spoke with emphasized that the important thing is that the asset transfer be big enough to be able to generate income – a good rule of thumb is the local value of two goats, but there is no magic size. The investment is also typically accompanied by enterprise development and money management skills provided by a coach to increase the likelihood of livelihood success (more below). - Basic needs: Support to stabilize participating households.

This support allows participants to fully participate in building their new livelihood so they don’t have to sell their asset to meet urgent needs. This typically comes in the form of cash or food transfers to meet consumption needs in the short run while the asset becomes productive. In some programs, the lump sum cash transfer primarily designated for the asset has come often enough to cover such needs, but for most government programs, this means ensuring participants are linked to any existing social assistance programmes. - Coaching: Intensive support to build agency, know-how, and hope.

Coaching sessions support participants to think differently about what’s possible, build their confidence, dream up new goals and pursue them, and navigate and respond to changing circumstances and challenges. This is accompanied by technical know-how to develop their asset into a productive livelihood and group-based peer support. In most cases, this also includes some connection with the wider community to reduce barriers and lower social exclusion.

Are we 100% certain of this? No. Despite the amount of evidence on the approach, little evidence exists on each question and on the effectiveness of the approach for different vulnerable groups within the extreme poor population. But we already know a lot, and the evidence we do have suggests that the ABCs are the foundation to the approach. To our knowledge, the approach doesn’t deliver the proven, clear, and lasting impact across contexts for people living in extreme poverty without them. But of course, we will continue to adapt as the evidence changes.

Do we have to use the framing of the ABCs? No. Use what works for your audience! However, given the ample evidence available, we argue that we need to clarify what is technically correct in this approach in order to achieve our scale goals. And the more we do this from the same “song sheet,” the easier it will be to ensure that various partners understand that we’re all talking about the same evidence-informed thing.

What’s next? In a world where aid budgets are being slashed, it is imperative to scale the proven Graduation approach to enable 700 million people to take steps along a pathway out of extreme poverty. The Graduation community is already well placed and doing development differently, but as we move into a new phase of global development, we will need to be even clearer about what works and how to scale together. As one voice we can point to a simplified program that has transformational impact in just two years (or less) that can build on and leverage many ongoing at scale programs and existing budgets. It’s too costly to not invest in this proven impact. We invite you to join us in that chorus.

References (for evidence review)

Alibhai, S., Buehren, N., Frese, M., Goldstein, M., Papineni, S. and Wolf, K., 2019. Full esteem ahead? Mindset-oriented business training in Ethiopia. Mindset-Oriented Business Training in Ethiopia. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (8892).

Alderman, H. Gilligan, D, Hidrobo, M. Leight, J, Mulford, M, Tambet, H. 2023. “Can a Light-Touch Graduation Model Enhance Livelihoods Outcomes? Evidence from Ethiopia.” International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Angelucci, M., Heath, R. and Noble, E., 2023. Multifaceted programs targeting women in fragile settings: Evidence from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Development Economics, 164, p.103146.

Argent, J, Augsburg, B, Rasul, I. “Livestock asset transfers with and without training: Evidence from Rwanda.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 108 (2014): 19-39.

Balboni, C., Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Ghatak, M. and Heil, A., 2022. Why do people stay poor?. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(2), pp.785-844.

Balboni, C, Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Heil, A., Mazet-Sonhilac, C. Sulaiman, M., Wang, Y. 2023. Poverty Reduction in the Face of Climate Change. Draft working paper.

Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Heil, A., and Sulaiman, M., 2023. Graduation. Draft working paper.

Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Das, N., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I. and Sulaiman, M., 2013. Can basic entrepreneurship transform the economic lives of the poor?

Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Das, N., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I. and Sulaiman, M., 2017. Labor markets and poverty in village economies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), pp.811-870.

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Goldberg, N., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Parienté, W., Shapiro, J., Thuysbaert, B. and Udry, C., 2015. A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries. Science, 348(6236), p.1260799.

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E. and Sharma, G., 2021. Long-term effects of the targeting the ultra poor program. American Economic Review: Insights, 3(4), pp.471-486.

Banerjee, A., Karlan, D., Trachtman, H. and Udry, C.R., 2020. Does Poverty Change Labor Supply? Evidence from Multiple Income Effects and 115,579 Bags (No. w27314). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Banerjee, A., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Trachtman, H. and Udry, C., 2022. Unpacking a multi-faceted program to build sustainable income for the very poor. Journal of Development Economics, 155, p.102781.

Barker, N., Karlan, D., Udry, C. and Wright, K., 2023. The Fading Treatment Effects of a Multi-Faceted Asset-Transfer Program in Ethiopia. IPR working paper series.

Bastagli, F., Hagen-Zanker, J., Harman, L., Barca, V., Sturge, G., Schmidt, T. and Pellerano, L., 2016. Cash transfers: What does the evidence say? A rigorous review of programme impact and the role of design and implementation features. London: ODI, 1(7), p.1.

Bedi, T., King, M., and Vaillant, J. 2023. Gender Targeting and Household Cooperation: Experimental Evidence from a Multifaceted Anti-poverty Program in Malawi. Working Paper

Bedoya, G., Coville, A., Haushofer, J., Isaqzadeh, M. and Shapiro, J.P., 2019. No household left behind: Afghanistan targeting the ultra poor impact evaluation (No. w25981). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blattman, C., Fiala, N. and Martinez, S., 2020. The long-term impacts of grants on poverty: Nine-year evidence from Uganda’s Youth Opportunities Program. American Economic Review: Insights, 2(3), pp.287-304.

Blattman, C., Green, E.P., Jamison, J., Lehmann, M.C. and Annan, J., 2016. The returns to microenterprise support among the ultrapoor: A field experiment in postwar Uganda. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8(2), pp.35-64.

Bossuroy, T., Goldstein, M., Karimou, B., Karlan, D., Kazianga, H., Parienté, W., Premand, P., Thomas, C.C., Udry, C., Vaillant, J. and Wright, K.A., 2022. Tackling psychosocial and capital constraints to alleviate poverty. Nature, 605(7909), pp.291-297.

Botea, I., Goldstein, M., Low, C. and Roberts, G., 2021. Supporting Women’s Livelihoods at Scale: RCT Evidence from a Nationwide Graduation Program.

Brudevold-Newman, A.P., Honorati, M., Jakiela, P. and Ozier, O.W., 2023. A firm of one’s own: experimental evidence on credit constraints and occupational choice. Center for Global Development.

Brune, L., Karlan, D., Kurdi, S. and Udry, C., 2022. Social protection amidst social upheaval: Examining the impact of a multi-faceted program for ultra-poor households in Yemen. Journal of Development Economics, 155, p.102780.

Brune, L., Goldberg, N., Karlan, D., Parkerson, D., Udry, C. 2023. “The Impact of a Graduation Program on Livelihoods in Refugee and Host Communities in Uganda.” Preliminary results, Innovations for Poverty Action.

Campos, F., Frese, M., Goldstein, M., Iacovone, L., Johnson, H.C., McKenzie, D. and Mensmann, M., 2017. Teaching personal initiative beats traditional training in boosting small business in West Africa. Science, 357(6357), pp.1287-1290.

Chowdhury, R., Collins, E., Ligon, E. and Sulaiman, M., 2017. Valuing Assets Provided to Low-Income Households in South Sudan. Discussion Paper.

Devereux, S., 2017. “Do ‘graduation’programmes work for Africa’s poorest?” What Works for Africa’s Poorest, pp.181-203.

Diwakar, Vidya, Tony Kamninga, Tasfia Mehzabin, Emmanuel Tumusiime, Rohini Kamal, and Nuha Anoor Pabony. “Pathways out of ultra-poverty: A mixed methods assessment of layered interventions in coastal Bangladesh.” (2022).

Fafchamps, M., McKenzie, D., Quinn, S. and Woodruff, C., 2014. Microenterprise growth and the flypaper effect: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Ghana. Journal of Development Economics, 106, pp. 211-226.

Gobin, V. J., P. Santos, and R. Toth. 2017. No longer trapped? Promoting entrepreneurship through cash transfers to ultra-poor women in northern Kenya. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 99(5), 1362–1383.

Haushofer, J. and Shapiro, J., 2018. The long-term impact of unconditional cash transfers: experimental evidence from Kenya. Busara Center for Behavioral Economics, Nairobi, Kenya.

J-PAL Policy Insight. “Building stable livelihoods for low-income households.” 2023 Update.

J-PAL SA, 2023. Going the Last Mile: Lifting ultra-poor households out of extreme poverty.

Kondylis, F. and Loeser, J., 2021. Intervention size and persistence. World Bank.

Morduch, J., Ravi, S. and Bauchet, J., 2012. Failure vs. Displacement: Why an innovative anti-poverty program showed no net impact (No. 32). Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University.

Misha, Farzana & Raza, Wameq & Ara, Jinnat & Poel, Ellen. (2018). How far does a big push really push? Long-term effects of an asset transfer program on employment trajectories. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 10.1086/700556.

Orkin, K., Garlick, R., Mahmud, M., Sedlmayr, R., Haushofer, J. and Dercon, S., 2023. Aspiring to a Better Future: Can a Simple Psychological Intervention Reduce Poverty?

Paul, B.V., Dutta, P.V. and Chaudhary, S., 2021. Assessing the Impact and Cost of Economic Inclusion Programs.

Rahman, A., Bhattacharjee, A. and Das, N., 2021. A good mix against ultra‐poverty? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Bangladesh. Review of Development Economics, 25(4), pp.2052-2083.

Rahman, A., Bhattacharjee, A., Nisat, R. and Das, N., 2023. Graduation approach to poverty reduction in the humanitarian context: Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of International Development.

Raza, W.A., Van de Poel, E. and Van Ourti, T., 2018. Impact and spill-over effects of an asset transfer program on child undernutrition: Evidence from a randomized control trial in Bangladesh. Journal of Health Economics, 62, pp.105-120.

Sedlmayr, R., Shah, A. and Sulaiman, M., 2020. Cash-plus: Poverty impacts of alternative transfer-based approaches. Journal of Development Economics, 144, p.102418.

Zizzamia, R., Das, N., , Dercon, S. , Haque, R. , Khan, M.N., and Pople, A. 2023. Experimental evidence on the role of coaching within bundled ultra-poor graduation programmes. Working paper.